A mental health and suicide post-covid snapshot

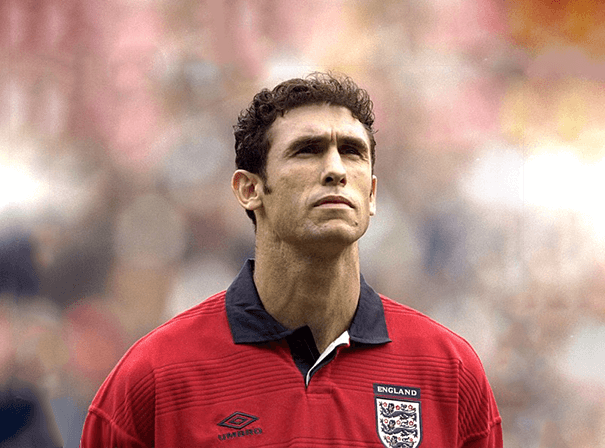

Let me preface this by saying I am not against lockdowns or their need. Recently witnessing thousands protest to the idea of frontline medical staff potentially requiring another vaccine (despite requiring rounds of them before entering a clinical environment) to continue to practice seems a tad much (to me anyway).

However, the way the lockdowns have been implemented and handled in the UK – and I would feel many may agree – have been far from ideal for the general health of the country – with very long periods of total isolation, with fear, stress and anxiety to boot, suddenly without access to many social norms to reduce or allay these fears.

“The status-quo”

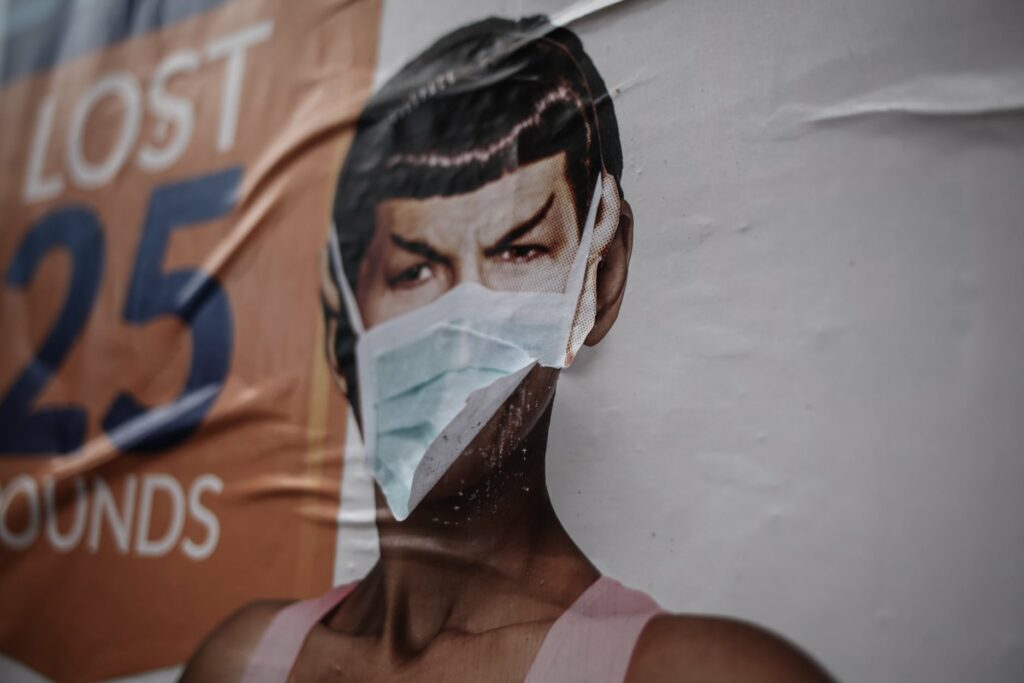

As of writing (Jan 2022) – it looks like Covid is going to become the status-quo and we may not face another lockdown, with restrictions being fully lifted as of the end of this month. Whilst I have some mixed feelings on that (is continued hand washing and mask wearing really that much of a hot thought whilst hospital admissions look almost at their highest? *as of the most recent Office of National Statistics charts) the feeling of certainty that we aren’t going to face the prospect of being locked away in our homes again and begin returning to a sense of ‘normalcy’ is certainly a positive one to be experiencing.

Sadly though, when it comes to the declining well-being of our national mental health, the damage appears already done over these last two, long years – and whilst I would say a lot of this was preventable, to a point, it is also nothing new:- the sad reality is that investment in mental health has been at the furthest reaches of on the back burner of our health system and society for far too long alongside social care (which often overlap) despite decade-long electoral promises of ‘parity of esteem’ – or an “equality” – between physical and mental health care.

This is regrettably becoming a larger and larger beast to tackle

This is regrettably becoming a larger and larger beast to tackle; the final result being thousands upon thousands of avoidable or early deaths happening each year to the impact of suicide or, complications with lack of appropriate treatment or placements in mental health settings, with many people feeling the loss of a loved one to a (mostly) preventable outcome.

Suicide is also a chain reaction, with the pain of losing a loved one in such tragic circumstances affecting, on average, twenty other people down the line.

We are social animals…

As human beings, we are social animals and are nurtured and reinforced by positive social bonds and interactions: and facing almost two years of minimal, broken or no interactions and tactile experiences with friends, loved ones, colleagues, the ‘outside’ world… what kind of detrimental effect does this have on us?

Studies in to loneliness and social isolation (which we’ve all been facing to varying extents) will tell you that on top of mass increases in preventable diseases like alcoholism to mental illness, suicide is also a much larger risk factor (Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2014) and more recent studies conducted on the impact of restrictions on young people show that they face considerable risk of high rates of clinical depression and anxiety when returning to the classroom.

It also suggests that preventive support and early intervention are key in preparing for these risk factors amidst the prospect of further restrictions (Journal of Academic Adolescent Psychiatry Nov. 2020) yet it seems that we, as a country with the worst public health crisis on our hands, may have missed the memo, despite Public Health being the biggest focus of many health and social care professions.

Even the most solitary individual (which, I will concede; definitely includes my socially grumpy self) will still thrive on human connection: this is how we have evolved in to being the advanced society we are today – through generational bonds forged to not just survive, but to adapt and flourish.

Coincidentally, our most time-tested and effective treatment methods for mental health issues also hinge on this concept and cornerstone of effective psychological interventions are encapsulated in these ideals; mutual cooperation, trust and planning in communication. However, despite living in an increasingly digital age, we have nothing that can fully replicate the nuances of face-to-face interaction which many have been deprived of for a long time now.

Suicide…

Suicide itself still oft a taboo subject; even amongst the realms of professional work in mental health. To disclose, in my own experiences sitting the other side of the chair as a client or patient (depending on the setting), I’d usually avoid the topic entirely when talking to a lot of mental health practitioners as the energy in the room would tend to shift upon mentioning the topic: I’d often experience a barrage of questions or would be treat differently, the result, being veered away from how I might have been presenting or wanting to talk about at that time (suicidal ideations don’t suddenly exist the moment you bring them up to someone else). This lead to, more than once, the prospect of being turned away for much needed treatment more for being honest and not filing neatly in to a sweet spot of ‘ill enough, but not too ill’.

In time I learned to ignore that part of myself, or risk not getting help at all – and whilst I know now that not all professionals and organisations operate like that; enough have given me pause to think otherwise. I was not solely my suicidal ideations. They were the end cause of many root problems and forgoing any treatment due to ‘risk’ palms off the problem to somebody else – and that somebody has ended up being nobody.

On the other side of the chair, for a client or patient to have trusted in me to share such details, I’ve found a both privilege and exercise in trust and hope that I’ve never misplaced that. Yes, it’s often shocking to hear if you had no suspicion, but it is a common human experience.

Being a professional in a multitude of spaces in and around the public, private and charitable mental health sectors for some time now; I’ve noticed that it is sadly far too common for professionals to have little, if any, training on the subject matter. To learn about the topic in any depth is scant to find and can be prohibitively expensive.

Mental Health First Aid courses were seen as a gold standard a few years ago, until the Government decided to rescind all public funding and now a course will set you back as much as £300 for the most in depth option: a sad premium for the knowledge in being equipped in the knowledge to avert a crisis or even help prevent a death.

I often see the Samaritans used as a catch-all signpost for suicide resources, but the Samaritans themselves are branded as an emotional helpline and are keen to shy away from the notion of being a ‘suicide hotline’ akin to what you would find in the United States and operate very differently from such (despite the UK parliament calling it “UK and Ireland’s largest suicide and self-harm prevention charity”).

At the core they have what many would deem a controversial self-determination policy – summed up, they won’t intervene with your decision to end your life and it is not unheard of for a Samaritan volunteer to listen to the last words of a caller.

However, if not Samaritans, then who? Support groups are almost non-existent and Crisis Teams are overwhelmed, chronically understaffed and underfunded.

Whilst ultimately, a lot of blame can fall upon the shoulders of chronic underfunding and a ‘one size band-aid’ numbers approach to streamlined NHS mental health services – this is not going to change overnight. For the sake of social mobility and progress, I’d say that it falls upon a collective responsibility of all of those working across health and social care to be aware of, knowledgeable to and understanding of the complexities of suicide and especially suicide prevention –listening ears and an open dialogue can alter the course of a life.

But is it all doom and gloom?

Most suicidal ideations (thoughts), even if chronic, are usually transient in nature and those going through the throes of suicide often want their pain to end rather than their life.

The vast majority of people who express suicidal thoughts do not go on to attempt their lives. A suicide attempt is not the be-all and end-all and many will recover, but it does not mean we should ever assume this to be the outcome or become complacent to those that do reach out (something I have experienced as a patient in years gone by, presumably through compassion fatigue).

This said, I can’t help but express that I find the way our society is treating suicide is that of an open secret in society – one we largely ignore; will talk about for one themed day of one themed year, express a quickly forgotten outcry and then leave things to carry on as they were.

Many social / media platforms even go to great lengths to silence the topic, going as far to blanket-censor any discussion of such or even ban the use of the keyword of ‘suicide’, despite the evidence stating that talking about suicide will not trigger an increased risk of such. (BBC 2014)

Silencing the subject of suicide is regressive and not in public interest to fight against mental health stigma. Instead of open and honest conversations on the topic, many are receiving their introduction and education from problematic, loud, big-budget serialised dramas that are poorly researched and romanticise the idea of suicide. (Psychology Today 2017)

The reality is that suicide, the largest killer in men under 45, is just too silent and I’d go as far as to suggest, brushed aside as an inconvenient truth that only happens to ‘other people’.

Whilst ‘general’ suicide statistics in the UK are shocking in themselves (with figures between 1 in 10 – 1 in 15 people attempting to take their own lives and as many as 1 in 5 having given suicide serious thought) – these figures don’t show the true statistic as suicides are under-reported and Coroners will often hesitate to place suicide as a cause of death in a person, often due to concerns around stigma and a desire to cause less ‘suffering’ to families instead (which arguably then ignores the elephant in the room for the sake of the emotional convenience).

However, the waters seem rather murky as to where we are heading with the impact of mental ill health and the looming mental health crisis which has shadowed public health in the UK for many, many years.

Suicide is the biggest killer in men and young people in the UK and has remained so for a long time, so I found it rather interesting that the Samaritans (July 2021) have stated that there isn’t much evidence to suggest suicide rates have increased during the pandemic, based on the released statistics for 2020 and rather boldly suggest suicide rates during the first national lockdown in England have “not been impacted in the way that many of us were concerned about” – yet we know demand for access to mental health resources, helplines and support has soared during the pandemic, with Crisis in mental health hitting all-time highs. (MIND 2020).

Each death should be a concerning number, in my view – especially if there are expected ‘additional deaths’.

Looking further in to this topic, suicide rates have indeed been touted as falling (by upward of 18%) – though -just as I’d guessed whilst discussing this with a colleague a few days prior – the data appears a small snapshot of part of the beginning of the pandemic and the statistics themselves are not up to date… due to just how many people are dying: not just from Covid, but from many delays in routine treatments, outright cancellations of lifesaving procedures, lack of access to GP surgeries and access to health professionals in general and ONS data on suicides (from the start of the pandemic) is only complete up until July 2020 because of death registration delays (Financial Times 2021).

With a lack of access to healthcare, how will these statistics look over this next year?

For a local example to ‘hit home’ – the Electro-Convulsive Therapy (ECT) treatment suite in Lincolnshire was simply shut down for a period of time due to a covid-related staffing crisis (as staff had been diverted from frontline mental health services to physical healthcare – pandemic or not, parity of esteem is still not a thing in 2022).

ECT itself is a last-line treatment for very severe treatment-resistant mental illness and it was simply stopped for a time to those living across one of the largest and most isolated counties in the UK. To put it simply; having your brain shocked in to having regular grand-mal seizures to ‘reset’ it, is not taken lightly by any means from practitioner to patient and whilst seen as a ‘safer’ treatment (compared to what is portrayed in the movies) these days, still comes with a slew of risk.

Those whom are in need of ECT are amongst the highest risk of suicide and ECT itself has been shown to reduce suicide risk (American Journal of Psychiatry 2005)

and whilst I don’t know what the individual experiences were from those had been waiting to receive this treatment at this time, or those that were even going through the treatment and had to stop, I don’t think it takes much understanding to suggest that this is an ethically sobering thought and feel for those that had to endure and I have often caught myself wondering where these people may be today – these people that you, who might be reading, have probably passed in the street or may even know of.

Indeed, my own ‘snapshot’ (albeit anecdotal) of a similar time during the pandemic as per the ONS suicide statistics during the pandemic shows a wider trend: those with the greatest need for mental health services were the least likely to get help (NIHR 2021) and regardless of what the most up-to-date ‘official’ literature I am able to glean, the fact remains that suicide is one of the biggest killers in young people in this country and is the leading cause of death for men under the age of 45, with close to ~6000 deaths a year or 18 suicides per day – and that’s only by the ‘on the books’ figures in which a coroner has registered a cause of death specifically by suicide and not what method of such ended the life.

So what does this say about suicide rates? Well, for what is out there, they’re certainly a very small snapshot in to an ongoing pandemic, for sure –and I don’t think it says anything of substance at this stage and dare I say, is premature to be suggesting anything concrete; a sentiment shared in large part by the Chair of the National Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention (Appleby 2021).

https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n834

As we’ve ventured in to 2022, with almost two years of ‘pandemic fatigue’ to contend with, I’ll be interested in seeing what the up-to-date set of ONS data suggests in suicide rates and how that reflects to how we are truly adapting to the invisible epidemic that is the suicide and mental health crisis in our country.

author: Zachary Kellerman

Therapist, Mental Health Expert by Experience &Mental Health Governor

www.linkedin.com/Zachary.Kellerman

Author recommended resources

Shout.org

Shout offers 24/7 text-based mental health support by trained volunteers

https://giveusashout.org/ or text: ‘SHOUT’ to 85258

Papyrus

Papyrus is a suicide prevention help and advice line open every day 9am-12am for younger people under 35

https://www.papyrus-uk.org/phone: 0800 068 4141

Samaritans

Samaritans offer 24/7 emotional listening support through a variety of means:

https://samaritans.org freephone: 112 123 or email jo@samaritans.org (Samaritans also offer drop-in one-to-one support in person, check your local branch to see opening hours)Free Short CPD for further understanding of suicide: https://www.relias.co.uk/hubfs/ZSACourse3/story_html5.html

References:Office of National Statistics. (2022). Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insights: Comparisons. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19latestinsights/overview. Last accessed 20th Jan 2022.

Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. (2014). Relationship Between Loneliness, Psychiatric Disorders and Physical Health – A Review on the Psychological Aspects of Loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 8 (9), 01-04.

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. (2020). Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. Journal of Academic Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 11 (59), 1218-1239.

Sandler, E. (2017). 13 Reasons Why “13 Reasons Why” Isn’t Getting It Right. Available: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201704/13-reasons-why-13-reasons-why-isn-t-getting-it-right. Last accessed 22nd Jan 2022.

Samaritans. (2021). What do we know about coronavirus and suicide risk? Available: https://www.samaritans.org/about-samaritans/research-policy/coronavirus-and-suicide/one-year-on-data-on-covid-19/what-do-we-know-about-coronavirus-and-suicide-risk/. Last accessed 23rd Jan 2022.

MIND (2020). Mind warns of ‘second pandemic’ as it reveals more people in mental health crisis than ever recorded and helpline calls soar. Available: https://www.mind.org.uk/news-campaigns/news/mind-warns-of-second-pandemic-as-it-reveals-more-people-in-mental-health-crisis-than-ever-recorded-and-helpline-calls-soar/. Last accessed 24th Jan 2022.

Kelly, J. (2021). Dip in suicide rates over lockdown may offer lessons for life after Covid. Available: https://www.ft.com/content/f098e2c1-0192-41fb-8c0a-de465a788b69. Last accessed 22nd Jan 2022.

BBC (2014). Does discussing suicide make people feel more suicidal? Available: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20140112-is-it-bad-to-talk-about-suicide. Last accessed 22nd Jan 2022.

Kellner CH, Fink M, Knapp R, et al. (2005). Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: a consortium for research in ECT study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5), 977-982.

Steeg, S. (2021). Many people with mental illness did not seek help during the first lockdown; research highlights unmet need. Available: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/alert/people-mental-illness-did-not-seek-help-during-first-lockdown-unmet-need-increased/. Last accessed 23rd Jan 2022.

Appleby, L. (2021). British Medical Journal: What has been the effect of covid-19 on suicide rates?. Available: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n834. Last accessed 22nd Jan 2022.